Eyes stare from the screen; we zoom out from stained-glass windows shaped like eyes. A superhero tilts her head to one side; we see a bronze bust tilted at the same angle, a purple mask over its eyes. The trunk of a car shuts; the trunk of a car opens. We zoom in on a detail of a white horse from an old painting of the genocide of Native Americans; a gentleman rides a white horse through a green countryside to his manor.

These are some of the striking visual moments in Damon Lindelof’s 2019 HBO series, Watchmen. The show is based on—really a sequel to—the 1986–1987 comic book series by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, a gritty, virtuosic metafictional critique of superhero culture—including the comic form itself. These abrupt shifts from shot to shot are in fact one effort to capture the aesthetic of the original. In an interview about the show, the director of photography, Gregory Middleton, said:

One of the transitional devices we wanted to use to echo the graphic novel is the match cut. In the comic you’ve got one panel with a character in the foreground and someone in the background. The next panel is the same character in the foreground, but they are somewhere else—or somewhere else in a different outfit…and you’re basically just jumping time because you’re really with the character and where their state of mind is, so the intervening time between how they went from here to there is irrelevant…. It’s a nice, clever way to keep you on point…. [We] worked hard on all the transitions in that episode to try and achieve that effect and make it interesting.

As Middleton says, a match cut—technically a graphic match—“jumps” rather than flows from shot to shot. Unlike a basic cut, which moves smoothly from one angle or moment to another in a single setting, giving us a feeling of continuity, a match cut lasts long enough for us to notice that two shots in different settings have similar shapes or movements—we make the leap to connect them, to relate two things separated by space, time, perspective. You could think of a match cut as a visual analogy or metaphor: a purposive claim that one thing is like another thing, a “perception of the similarity in the dissimilar,” as Aristotle put it. Or you could think of a match cut as a visual pun: a trifling way to play with the fact that two things echo each other. Either way, as a technique for juxtaposition, match cuts raise two questions: What’s the relationship between the things juxtaposed? And how is the juxtaposition itself justified?

You can justify juxtaposition aesthetically, the way Middleton does: as nice, clever, interesting. The match cut between the eyes and the stained glass is indeed very pretty, between the opening and closing of the trunk deft. But what about the match cut between a painting of the genocide of Native Americans and a shot of a gentleman riding his horse to his manor? It seems to be making a point about the relationship between empire and mass murder. As the show progresses, we learn that the gentleman is essentially a colonial master over a race of amenable clones on a moon of a distant planet, and that decades earlier, when he was still on earth, he killed three million people, ostensibly to prevent the imminent nuclear holocaust of World War III.

But what are we to make of this comparison between a fictional genocide justified by utilitarianism and a real genocide justified by Manifest Destiny? What are we to make of the juxtaposition of large-scale acts of violence as such, a kind of match cut of historical traumas? Here’s where the technique of juxtaposition gets tricky. Watchmen puts disparate things next to each other and admirably eschews didacticism by asking us to decide the relationship between them. But is that bridge a metaphor or a pun? Is it good art or just good fun?

What’s the difference between good and fun when it comes to art? Good is an egg—a slippery, laden, fragile word. Good works of art aren’t necessarily about good people—in fact, they’re usually not—nor are they necessarily created by them. Fun is a gun—a shiny, blunt, punchy little word—easy to pull, hard to look away from. Fun seems universally appealing, but it can quickly turn cruel. Good and fun are both relative—to the viewer, to history, to culture—yet they’re common, familiar feelings, recognizable terms we still like to use because they gesture at our evergreen debates about the relationship between art and ethics. You can map good vs. fun onto: aura of authenticity vs. mechanical reproduction; high art vs. mass culture; midcult vs. mass cult; avant-garde vs. kitsch. Every binary implies a hierarchy one way or the other. Critics have generally (though not always) favored the good over the fun, while mass audiences have made a case—with their numbers if nothing else—for fun.

Advertisement

The original Watchmen comic book is all about the collision of the good and the fun in that classic American arena, violence. It opens like this: “Dog carcass in alley this morning, tire tread on burst stomach…. The streets are extended gutters and the gutters are full of blood and when the drains finally scab over, all the vermin will drown.” These lines come from the journal of a superhero named Rorschach, who is a violent racist and misogynist. They introduce the metacomic self-awareness characteristic of Watchmen: “gutters” is industry jargon for the thin gaps between the frames of a comic book page. Readers hop across them, filling them in with missing scenes and implications, which in genre comics are more often than not literally full of blood. This is the most basic form of juxtaposition in a comic book; Watchmen immediately calls attention to it.

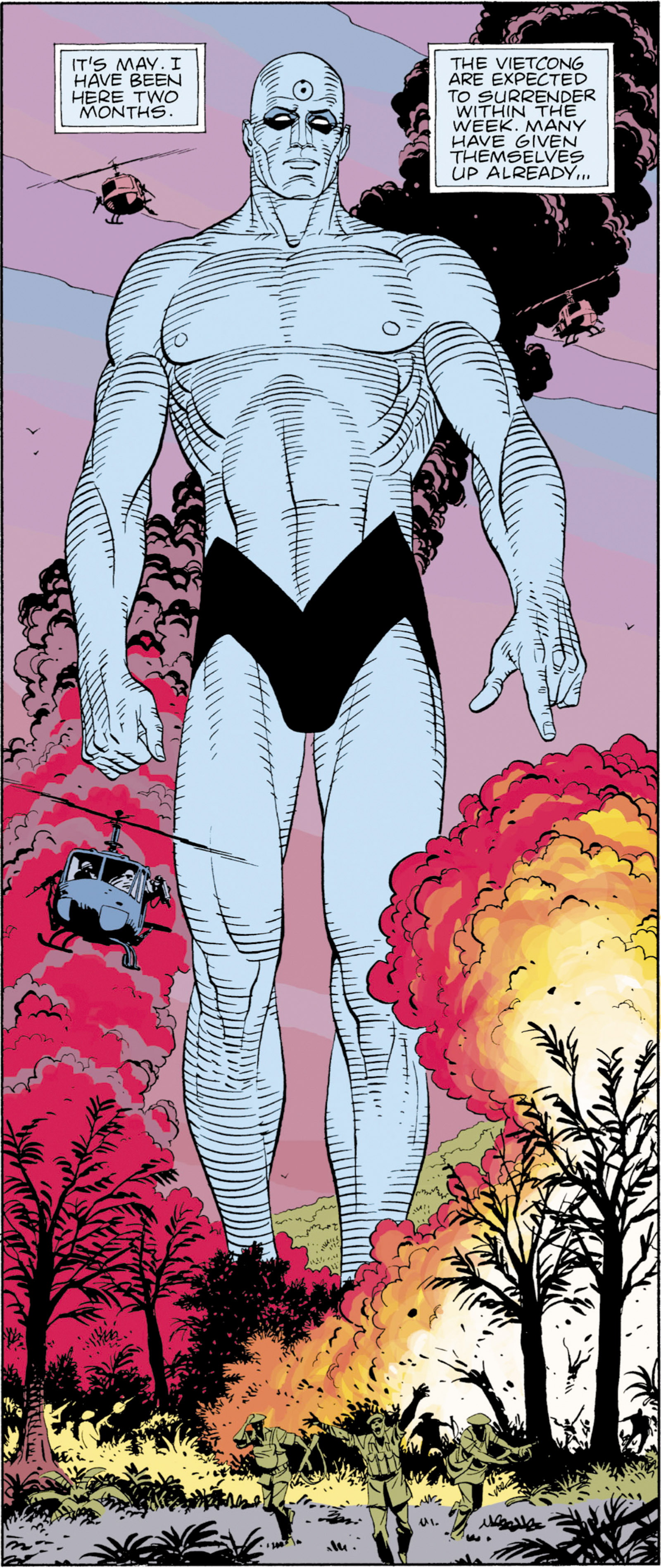

Rorschach has just discovered that a superhero named the Comedian has been murdered. As he investigates, he visits other superheroes, whose backstories then unfold over the course of the comic. Watchmen takes place in an alternative universe where two generations of masked heroes—the Minutemen and the Crimebusters—emerged to fight crime, only to be banned in 1977 as dangerous vigilantes. The crimefighters we learn about include fascists hungry to harm; abuse victims seeking revenge; kinksters looking for masked love; outcasts with delusions of grandeur; the smartest man in the world, Adrian Veidt; and only one genuine superhuman, Dr. Manhattan, who was accidentally disintegrated in a nuclear reactor and reconstituted himself into a omnipotent, omniscient glowing blue giant. With his supernatural help, the US wins the war in Vietnam and incorporates it as the fifty-first state. On the cusp of World War III—a looming nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union—Veidt drops a gargantuan squid on New York City and claims it’s from another dimension, killing millions and scaring the world’s nations into joining together for protection.

Watchmen is a sophisticated inquiry into the ethical implications of its own form—the flash and bang, the prurience and violence of comic books. The superheroes save the world, but at what cost? Or as graffiti on the walls of its alternate New York City puts it, Who watches the Watchmen? The line quotes the epigraph to an appendix of the 1987 Tower Report that Ronald Reagan commissioned to investigate the Iran-Contra scandal, which in turn quotes and translates Juvenal’s Satires from the second century AD: “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes.” This allusion within an allusion captures the problem of moral contamination with which the comic is most concerned: Can violence redress or prevent violence?

The Watchmen comic ends in 1985, just as “RR” is running for President of the United States—not Ronald Reagan but Robert Redford. An arbitrary historical coincidence yields a pun that works as cutting political satire: it could just as well have been the other cowboy movie star. The Watchmen show is set in 2019—and Robert Redford is still president. The show uses the occasion of his name to conjure a controversial reparations program called “Redfordations.” This pun is a stroke of genius: a President Redford’s name would indeed get attached to a progressive program (as with “Obamacare”), which would indeed cause frustration among white supremacists. The pun soars even higher when you realize how flat “Reaganations” would fall, and because Redford never makes a cameo, the satire on race relations can float and sting rather than getting bogged down in real politics. The show best captures the satirical spirit of the comic when it offers what Thomas Pynchon calls the “high magic to low puns.”

The show is a great example of the promise and paradox of “prestige television”: a high-quality HBO series adaptation of a work in what was once considered the lowest, pulpiest, mass-iest of forms. It is good and it’s fun. But the Great Media Shift of the twenty-first century—toward the hegemony of Hollywood action movies and the Third Golden Age of Television—has only intensified the questions about the representation of violence that the old Watchmen comic obsessed over in the Eighties. The new Watchmen show is thus also an example of the clusterfuck of fun aesthetics and good politics, the clash of the slick and the woke that we’re seeing in so much contemporary cultural production. This is nowhere more evident than in how the show deals with blackness.

Advertisement

Watchmen’s take on race illustrates the continued difficulties of using fun (clever, nice, interesting) comic book techniques to address intractable, complex questions about the good. The comic book’s political critique was aimed squarely at America’s questionable involvement in international conflicts: the Vietnam War, the cold war, the Iran-contra affair. The show takes up a more homegrown fascism: American white supremacy. Lindelof, who is Jewish, spoke in an interview about the need to change the structure of the production, rather than simply sprinkling the casting with superficial diversity:

I could no longer deny that our country is completely and totally divided by race. This seemed to be the new Cold War and there is a reckoning that should be happening. As a white man and a beneficiary of this system, do I approach this with guilt and shame or can I approach it from a vantage point of service?… I brought together a writer’s room, where the white dudes—there were only four of us out of 12 people—had to sit back. I had to hear some hard truths.

One of those truths came out in another interview: the other writers convinced Lindelof that the show needed to buck political correctness, to show police officers using the word “nigger”: “We didn’t want to pull any punches. We didn’t want to be flippant with the material.”

The show begins with a series of race reversals. First, an invocation of The Birth of a Nation, the film that was both the birth of mass cinema and the rebirth of the KKK. A sepia silent film plays in the opening moments of the first episode: a hooded hero on a steed chases a villain, who turns out to be the white sheriff of the town. He lassoes the man to the ground, then removes his hood to reveal that he is black. A white boy points and exclaims excitedly, “That’s Bass Reeves!”—a genuine historical figure, the first black deputy US marshal in the west, long thought to be the basis for the Lone Ranger.

The camera roams out of the film to its screening, where a lone black boy sits in the audience, while a black woman, his mother, plays the soundtrack on a piano near the stage. The scene of happy movie-watching is swallowed up in a harrowing sequence of violence and escape. This is Tulsa, Oklahoma, the summer of 1921, when white supremacists bombed the city’s flourishing Black Wall Street. The boy is loaded on the back of a cart inside a wooden box, soon riddled with near-miss bullet holes, through which he watches a car dragging the bodies of lynched black men. An explosion. The boy wakes up alone in a field, and finds an abandoned baby girl, whom he wraps up in an American flag. The flames light up the horizon behind him, the scene colored in a patriotic red, white, and blue.

Then we shift to an American chase scene of a more recent ilk: the traffic stop. Except this time, the man driving along, listening to hip-hop, is white; the cop who pulls him over is black, evident even under his mandated yellow mask—part of Lindelof’s expansion of Watchmen’s alternative universe. The cop goes back to his car to request permission from the dispatcher to unlock his gun—another alternative feature—but despite receiving the all-clear, has trouble removing it. He looks up as the white driver shoots him through the windshield. And we’re back to reality: a black man with an authorized firearm, shot dead, riddled with bullets, covered with blood, inside his own vehicle.

As the show goes on, the political implications of its race reversals pile up a little messily. We meet Angela Abar, played with extraordinary emotional precision by Regina King. Angela is a black cop with three adopted white children. She grew up in the fifty-first state, and now runs a Vietnamese bakery in Tulsa as a front—she’s undercover. She dresses up as a nun, codename Sister Night, when she’s on duty, busting heads and torturing suspects. She’s best friends with the white chief of police, who is played with disarming charm by Don Johnson. He teases her for not showing up to watch Black Oklahoma, a faithful rendition of the musical starring an all-black cast. All these reversals feel like good fun. The soundtrack and edits whenever Angela gets outfitted as Sister Night have a pumping, action-movie energy. When the chief of police finds her in his office, she’s sitting in his chair, feet up on his desk, a badass, our hero.

Angela believes in a black-and-white moral universe, as she tells her son. We learn that the boy’s biological father was her police partner, who was killed along with his wife in what is known as the White Night, during which men wearing Rorschach-inspired masks slaughtered cops in their homes. This trauma is the reason cops now wear masks to protect their identity. It is also why Angela is so close to the chief of police: they were two of the few police officers who refused to quit after the White Night. The instigating incident for the plot of the show comes when Angela is called to witness his dead body, hanging from a tree, at the base of which sits a 105-year-old black man in a wheelchair. “I’m the one who strung up your chief of police,” he tells her. It turns out that he is Angela’s grandfather (played with wry gravitas by Louis Gossett Jr.), and that he was one of the original Minutemen, with a decades-old axe to grind.

A black woman is our central hub, around which everything revolves. This very fact is enough to reverse a long white male history of comic books and franchises. But every reversal, like a spinning wheel, picks up residue. The twenty-first-century imperative to (finally!) give us sympathetic black heroes comes up against the critical bent of Moore and Gibbons’s older comic. That is to say, the masked heroes in the original Watchmen were clearly antiheroes. Their respective motivations for putting on masks to fight crime were all cast in doubt. The comic relentlessly asked, Were they a righteous militia (the “New Minutemen”) or were they perverse, violent vigilantes? We can see the show’s tonal shift in how one of the original heroes, Laurie Blake, diagnoses Angela: “People who wear masks are driven by trauma; they’re obsessed with justice because of some injustice they suffered, usually when they were kids. Ergo the mask. Hides the pain.” Blake herself doesn’t believe trauma excuses superhero violence; as she later quips, “You know how you can tell the difference between a masked cop and a vigilante? Me neither.”

But the show dwells on Angela’s trauma in a way that seems to justify rather than diagnose her vigilantism. The plot meticulously unmasks Angela’s pain, and her grandfather’s, and—this is crucial—goes on to juxtapose them. This hinges on a science-fictional invention: “Nostalgia” pills that store memories and allow you to reexperience the past. Angela swallows a whole bottle of her grandfather’s Nostalgia pills at once, sending her into a kind of waking coma in which she experiences his life from within. A remarkable feat of cinematography, this episode-long sequence takes juxtaposition to its logical extreme: conflation. Angela doesn’t just witness or hear about her grandfather’s traumas, which take place in a black-and-white past, she feels them: the episode switches between her grandfather as a young man and Angela acting in his place. As if combining a match cut and a splice cut, the camera pans away from him and returns to her, as they remember being that little boy orphaned by the Tulsa bombing, as they become a black officer in a racist white police force, as they become a superhero, one of the first: Hooded Justice.

The episode cleverly picks up certain details from the comic, in which Hooded Justice is presumed to be white—his refusal to remove his mask, the unexplained noose around his neck—to give him a new origin story. When he tries to arrest a man for setting a Jewish deli on fire, his fellow officers release the arsonist. It turns out that they, like many cops in real life, belong to a white supremacist organization—this fictional one is called the Cyclops, and is using a form of hypnosis to get black people to murder each other. The climax of the episode comes when Angela undergoes her grandfather’s horrific experience: white cops assault him, cover his head with a hood, wrap a noose around his neck, string him up to a tree, let him hang for excruciating seconds—then cut him down.

Even after she comes out of her empathic fugue state, the show continues to intercut shots of Angela’s own originary trauma—watching her parents get blown up by a terrorist’s bomb when she was a child in Vietnam—with shots of Hooded Justice’s experiences. The continuities between the two characters work as a matter of plot: the Cyclops group from her grandfather’s youth has recently reemerged in the form of the white supremacist Seventh Kavalry. Angela is part of a lineage of traumatized, righteous black police officers forced to don masks and maintain a secret identity. At the Greenwood Center for Cultural Heritage in the show’s alternate Tulsa, a video of Treasury Secretary Henry Louis Gates Jr. offers “condolences for trauma you or your descendants may have suffered.” At a meeting of those who suffer from “extradimensional anxiety,” a black man explains how his mother’s experience the night the squid attack caused three million people to suffer “a horrific, traumatizing, and inexplicable death” may have resulted in “genetic trauma” now locked into his DNA. Lady Trieu—a brilliant, ludicrously wealthy Vietnamese scientist who is on a hubristic mission to save mankind—clones her mother, then raises that baby as a daughter, feeding her with Nostalgia pills so she can “remember” the trauma of the Vietnam War.

The Tulsa race massacre, the Holocaust, the Vietnam War, the ever-prophesied American race war to come. Does the juxtaposition of these conflicts reflect history’s eternal return? Does it imply a “both-sides” victimhood competition? Or does it suggest a basis for solidarity between, say, the Vietnamese and the African-American victims of American genocide? Watchmen occasionally posits that we can forge connections with others on the basis of purportedly shared or analogous traumas. This is its form of political match cutting—histories of violence are juxtaposed; we are tasked with bridging them in a meaningful way. Hooded Justice wants Angela to take his Nostalgia pills rather than hear his story because “she’s not gonna listen, she’s gotta experience things by herself.” While Angela recovers from that experiment, Lady Trieu’s daughter runs another one on her for a dissertation about “the adaptive function of empathy and the role of rage suppression in social cohesion.”

Yet comparing her trauma to her grandfather’s—finding “the similarity in the dissimilar”—leads Angela toward neither rage suppression nor social cohesion. She is a righteous warrior! The show simply surrounds her with other righteous warriors. It turns out that not only was her grandfather a cop and a vigilante, and her father a soldier, but her husband is secretly Dr. Manhattan, the superhuman superhero who won Vietnam for America by committing genocide there. Having left earth to its own devices for years, the superhero has returned and, for somewhat inscrutable reasons, falls in love with Angela and inhabits the body of a mortal so he can marry her (she chooses a dead black man for him to reanimate; Yahya Abdul-Mateen II imbues the famously neutral character with a cool, slow charisma). They decide he should live under an amnesiac spell—one partner seeing the future turns out to be a bummer for relationships; during a fight, he tells her, infuriatingly, that he’s standing on the surface of their swimming pool because “it’s important for later.” While it’s depicted as a solid and vibrant marriage, it also exposes Angela and their children to the threat of the Seventh Kavalry, which is trying to steal Dr. Manhattan’s powers. She proves her love for him by trying to kill them.

Angela’s newfound understanding of trauma simply joins the host of motivations the show provides her with to kill, to torture, to be party to the gruesome destruction of both the white supremacist bad guys and Lady Trieu, to accept and enact violence. The show’s investment in trauma suggests that it wants to be politically good, but it can’t relinquish the fun of a gun-slinging, finger-cracking hero. In the final episode, Angela and her grandfather end up in the theater from the first episode. As a black spiritual hums on the soundtrack, Hooded Justice perorates about the legacy of being the victim—not the complicit or recruited perpetrator—of violence:

My mama played the piano right over there. It burnt, too. Last thing I saw before my world ended was Bass Reeves, the black marshal of Oklahoma. Fifteen feet tall in flickering black and white. “Trust in the law,” he said. And I did…. That’s why I became a cop. Then, I realized, there was a reason Bass Reeves hid his face. So, I hid mine, too. Hooded Justice. Mm. The hood. When I put it on, you felt what I felt? Anger. Yeah, that’s what I thought, too. But it wasn’t. It was fear and hurt. You can’t heal under a mask, Angela. Wounds need air.

It seems the problem with vigilantism isn’t the violence; it’s the anonymity. All that trauma-sharing gives way to a pat and slightly disingenuous revelation about healing. Mask or no, Angela’s still a cop, still the wielder of state-sanctioned violence, and now with a personal legacy to motivate it.

The king is dead, long live the king! With this proclamation, first made in 1422, when Charles VII succeeded Charles VI, the passing of an old order is made simultaneous with the advent of a new one. Or nearly simultaneous. There’s that comma. That blip, that pause, that tiny vacuum called an “interregnum” by the Romans, who treated it as a suspension of the polis and the law. It’s a weird and ghastly thing, the comma that sits between death and life, splices the void and the surge of power, makes of the king a doppelgänger. Slavoj Žižek’s 2010 translation of a line from Antonio Gramsci’s 1930 prison notebooks captures it well: “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born: now is the time of monsters.”

This is where we are now when it comes to cultural production, in the gap between TV and prestige TV, comic books and comic book culture, diversifying art and decolonizing it, fun art and good art. We are in the interregnum between an old order and a new, and it’s bursting with monsters. “Monster” etymologically derives from the Latin word monstrum, which itself derives from monere, “to warn.” The original Watchmen cast itself as a warning. Any artwork that insists on issuing warnings must depict—must immerse itself in—that which it is warning us against. How do we fight the monsters that we ourselves conjured in the first place?

On the surface, both Watchmen projects have the same arc: a murder prompts an investigation of the hero’s past that reveals that there’s no form of heroism—not even a knightly fantasy of law and order—that isn’t drenched in blood. As a young girl, Angela identifies the terrorist who bombed her parents, then asks to listen when he gets shot by the cops. She’s rewarded with a badge and a future job offer. As a cop in Vietnam, she falls in love with Dr. Manhattan, knowing he committed the genocide that motivated that man’s act of terrorism. As Sister Night, she beats suspects during interrogation. As a mother, she reminds her adopted son that they live in a black-and-white moral universe. The show seems to justify Angela’s violence with her identity and her history as a black American woman. What if it had been bold enough to say outright: she too is a monster? What if we’d been asked to see her—as we are asked to see every superhero in the comic—as an antihero?

Instead, the show blesses her heroism with a supernatural gift—an egg that Dr. Manhattan leaves for her, in which he has stored enough of his matter, he says, that anyone who consumes it will have his physical and psychic powers. In the last moment of the show, standing at the edge of that swimming pool where they had their lovers’ quarrel, Angela cracks and swallows the egg, then hovers her foot over the water. The screen goes black. When she steps down, will she plunge or will she balance? Will she turn a radiant blue? And what will that glow, so close to the blue of police car lights, mean about her bodily matter? Watchmen doesn’t show that moment, and not just because it needs to end on a note of irresolution—that ambiguity to which it commits as a good aesthetic and a fun cliffhanger. Watchmen can’t show that moment because the implications of this juxtaposition made manifest would be both silly and a little grotesque: black life matter might become blue life matter, and if she absorbs Dr. Manhattan’s powers, perhaps all life matter as well.

We are desperate for black heroes. We have been starved for over a century. Putting a black woman—black pride, black love, black speech (King knows her way around the piquant varietals of “motherfucker”)—at the center of a superhero show is a long-awaited reversal of the usual story. We’d hate to see that unabashed blackness blemished with quibbling about the relative righteousness of violence. But what if Watchmen had refused the trend of casting black actors as cops, a double distortion that flaunts statistical reality and uses “diversity” to humanize the brutal practices of the state? Or what if, premise conceded, the show had been brave enough to give us a glimpse of Angela as a monster, a vigilante glowing with the unchecked power of police blues? What if it had taken seriously the fact that all of us—even black women with a history of trauma—can be recruited into perverse and unjust state violence through the illusion of heroism?

Hegel argued that tragedy emerged not from a conflict between good and evil, but from a conflict between two goods. In Antigone, one of these goods is the heroine’s love for her brother; the other is the law, which bans her from burying him. She buries him anyway and is killed:

That is the position of heroes in world history generally; through them a new world dawns. This new principle is in contradiction with the previous one, appears as dissolving; the heroes appear, therefore, as violent, destructive of laws. Individually, they are vanquished; but this principle persists, if in a different form.

Angela, too, is split between love and law, but when she violently destroys laws (when she tortures witnesses, for instance) she in fact doubles down on the murderous logic of the law. The ultimate testament of her love is shooting a bunch of racists who are trying to kidnap her genocidal husband. The show does emphasize the futility of her choices: black cops still get killed by white supremacists, Dr. Manhattan dies anyway. But I think it makes a mistake, that it in fact condescends, when it pulls its punches and its punchlines, when it lets an avenging Angela triumph—unvanquished, violent, heroic, full of justifications about justice, and perhaps soon to be all-powerful—without asking: What is her principle? And in what form will it persist?

This Issue

April 9, 2020

Bigger Brother

Stuck